Why I Dropped Out of College and Went to Yeshiva.

Why I Made the “Unorthodox” Decision to Live with Orthodox Jews.

Shalom Chaverim,

For the last two years, I attended one of the top party schools in the country, but I hated partying. I had three different majors, but I was passionate about none of them. I had close friends, but I felt like an outcast. I couldn’t get up in the morning, which meant I was late for morning classes almost every day.

I had to make a change, and now, I am halfway across the world in a Yeshiva in the most talked-about country in the world, Eretz Yisrael.

My Childhood.

Growing up, I had all the creature comforts. I didn’t have to worry about money; my parents had already saved for my college education, and despite my many health problems, I never had to worry about healthcare bankrupting my family.

While I had material foundations, I didn’t have what truly mattered: faith and a sense of community.

When I was 15, my parents' divorce destabilized everything for me. I didn’t have to be disciplined because my parents would compromise their parenting to gain favor from my sister and me. The divorce nearly ruined the exemplary relationship I had with my sister because one of my parents used me against her.

I had to grow up faster, but that didn’t necessarily make me a mature, stable individual.

This period of turmoil left me confused about everything. I questioned almost every aspect of my identity, struggled to make my own decisions, and probably wasn’t the best person to be around.

Somehow, I didn't get addicted to drugs, become transgender, or join a political cult like many people my age. My life was atomized, but somehow I found new hope.

The Lifeline.

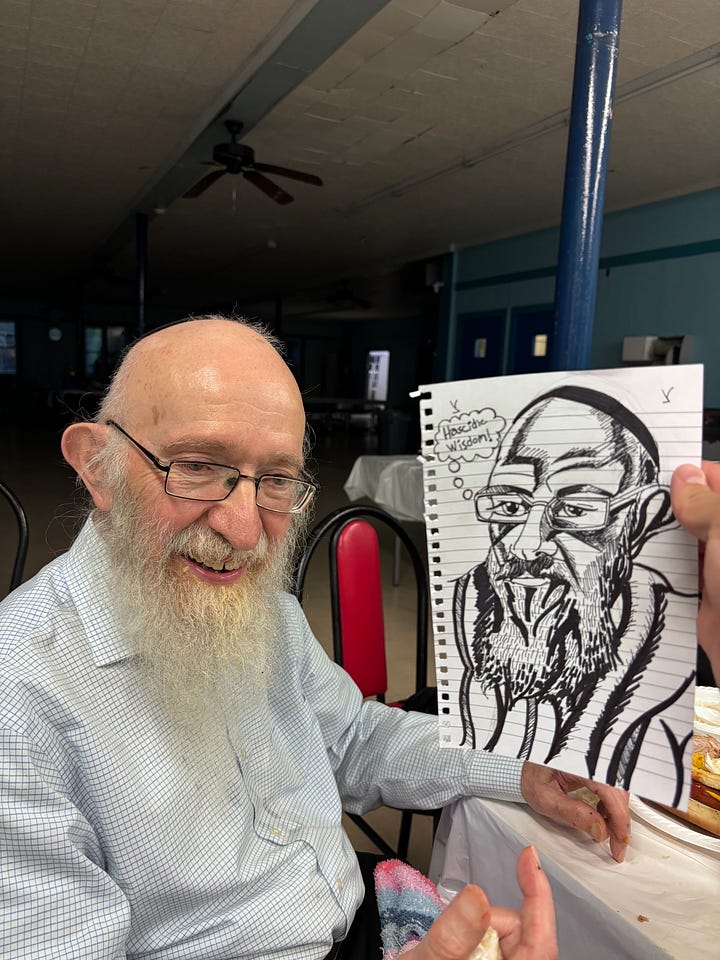

The only person I felt truly understood what I was going through was my local Chabad Rabbi. I would have been completely isolated if he weren’t there for me every step of the way, always available to offer wisdom, company, and support.

Some may call this “predatory indoctrination,” after all, cults generally go after atomized individuals because they are more susceptible to programming. But unlike cults, exposure to my Jewish roots made me more independent, analytical, and decisive.

This is because Judaism isn't a culture of submission or guilt like Islam and Christianity; it is a culture of questions and debates. While there is consensus in the Torah, such as Rambam’s 13 principles of Jewish faith, even within Orthodox communities, there is a ton of diversity.

There are Chassidim, Litvish, Kabalists, Modern Orthodox, Dati, and more. Despite their diverse opinions, the family remains relatively harmonious compared to others of different faiths.

That is why I don’t consider Judaism to be a religion; a religion is like a business, and you can always return the product. But Judaism is a nation; once you are a citizen, either through birth or conversion, you are part of the greater community. And unlike my own home, where there was no shalom bayit, they managed to create it even across different sects.

Freedom in Structure.

At first, I found these traditions silly and outdated. But as I observed how these positive and negative commandments shaped Orthodox Jews, I found myself envying their discipline. I learned over time that there is immense freedom in structure.

Going to the Mikvah, keeping kosher, praying three times a day, and studying a page of Talmud daily were not just habits but exercises to strengthen one’s character.

Do norms play a role in their behavior? Absolutely! There is societal pressure to conform, leading to various unhealthy issues, including reckless decision-making, self-loathing, and shallow observance. This is a separate issue I may discuss in the future.

But there is no point in throwing away good values and traditions. Jews should impart these habits through inspiration rather than pressure. And they need to be embraced with an understanding as to why they exist beyond just “tradition.”

For example, in my secular past, marriage was treated as “important” because it was what people had always done. That reason to get married leads to resentment and nihilism when things start to fall short of expectations.

That is how I felt after seeing my parents ’ nasty divorce. I saw marriage as a scam. If 50% of marriages end in divorce, what is the point of a lifelong commitment? What is the point in putting any work into a marriage when divorces can turn out so ugly and traumatize the kids?

But I regained hope when I saw how my Rabbi treated marriage as more than just a contract or tradition, but a work of art. Like a painting in a museum, it requires constant maintenance and an understanding of the craft so it stays in good condition.

Life isn't a romcom, as I clearly learned from my parents' divorce, but it doesn’t mean relationships have to be sad and gray. Ideals are intended to be aspired to, and even if there are failures, it doesn’t mean it has to end in giving up.

Redefining wealth.

Eventually, after getting close to my Chabad rabbi in university, I realized he possessed true wealth. He didn’t have the nicest car or the latest computer. But, as the Mishnah teaches: “Who is rich? One who is happy with his lot.”

Success is about creating community, building a family, and being happy with what you have—not how much you possess.

Their loyalty to their family, community, and traditions is what made them rich. And I realized that, while it was counter to everything I thought growing up, following these traditions may be a path to breaking the cycle of intergenerational family failures.

My Personal Sinai.

In the summer of 2024, I made an unorthodox decision to live for 40 days in the Catskills Mountains of New York and learn the fundamentals of Judaism with orthodox jews. This Program is a Jewish summer fellowship offering a stipend for learning Torah.

This experience changed me, as it was the first thing I did without my parents' influence. My attention span rapidly increased from constant Torah study. I felt myself becoming more inquisitive and found myself very motivated and hopeful.

When I returned to college after everything I had been through, I felt like I was deprived of air. I was separated from my friends. I saw myself assimilating and losing the good habits I developed in Yeshiva, like Torah study, kashrut, and prayer, and I felt isolated because I realized how much my values differed from my neighbors.

College is important, but it isn’t for everyone. And I realized I needed to delve deeper into the part of myself that the Catskills Mountains shaped before I ever returned to college.

I did some research and decided to take a “leave of absence” despite having no intention of returning to the same university. I signed up for the J101 program at Ohr Someyach Yeshiva. It’s a part-time Yeshiva and part-time internship, allowing me to balance both parnassah and Torah.

The New Me?

I now feel like I have control over my life and am hopeful again. I will miss my family, my dog, my friends, and my rabbis, but I know that this is what I need to be the version of myself that G-D wants me to be.

Do I see myself with payot and a black uniform? Probably not, but I am open to the idea.

Now I feel free to explore myself. For the second time since last summer in the mountains, I am doing what I want—not because I feel society needs me to, but because I am following my dreams.

May you grow in Torah Avodah and Gmilus Chasadim

I am excited for your new adventure